The Power in Owning Your Name

To mark Black History Month, we explore why names should be pronounced correctly

To mark Black History Month, we wanted to talk about names and why we should all make an effort to pronounce them correctly in the workplace. We hear from THE FIFTH’s Apprentice Nana Akosua Frimpong who explores why her name holds meaning to her as a Black woman – and how creators are now using their platform to speak out on an issue that has been overlooked for years.

Imagine there’s a new starter at work. They introduce themselves as you shake their hand and realise you didn’t hear their name clearly enough. You ask them to repeat it, not once but twice, and then say it back to them again incorrectly. The new employee might shrug it off and accept a somewhat close enough variation of their name to avoid awkwardness – but they shouldn’t.

Your name is your identity. It is what your family, friends, colleagues and even strangers use to call upon you. Our names have meaning, whether it is cultural, religious or personal, and are a part of who we are as an individual.

Repetitive mispronunciations can lead to people not feeling important or worthy then, and it can induce annoyance because the same people can easily pronounce Euro-centric names such as Niamh and Llewyn.

This has driven some ethnic minorities to anglicise their name for the sake of being accepted. Failing to call someone by the name given to them is the eradication of the culture and heritage that has been bestowed upon them, and not only undermines inclusivity but can affect the person’s emotional well-being.

When you refuse to take the momentary effort to pronounce someone’s name correctly, it suggests your own discomfort with their identity and essentially shows that they aren’t important enough to expel the energy – making it a form of microaggression.

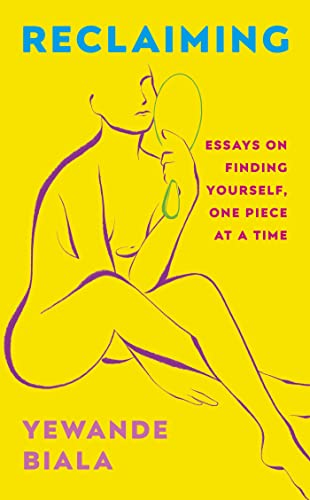

Many influencers have come forward in support of owning their names. Yewande Biala from Love Island wrote for The Independent and has even written a book, Reclaiming, as an ode to reclaiming oneself a piece at a time.

After experiencing teachers mispronouncing her name at school, Yewande wrote that she vowed to give her future children European or normative names. When she told this to her mother, her response was: “There is power in your name, and power in the tongue who speaks it. Raise your head, smile, and boldly tell them that your name is Yewande, daughter of Biala.”.

As a Black Woman with a strong African name, I have faced multiple forms of racism and microaggressions. My younger self barely understood the relevance of shortening my name. It wasn’t until my twenties that I learnt the true reason behind the shortening of my name: I chose to make it easier for others to pronounce my name by forgoing the entirety of my first name. I chose to put others’ comfortability first before my own.

I distinctly remember a point in my life when I would hate to introduce myself because others couldn’t take a moment to ask or learn to pronounce my name correctly, instead, they chose to ‘remix’ my name.

I remember being uncomfortable hearing my name be pronounced differently and worse the dismissive attitude of the person when I tried to correct them. I learnt quickly that it would be easier to introduce myself with an easily pronounceable version of my name than to ask people to learn my full first name.

As I entered my twenties, however, I realised that no one knows who I am. Most people call me Nana and a fair few outside my family know me as Akosua or Akos yet not many know me as Nana Akosua.

Although I still go by Nana, I no longer choose to forgo the entirety of my first name when introducing myself. My name has meaning and it is an embodiment of who I am. Nana means Queen/King and Akosua means Sunday born translating to Queen of Sunday.

To truly understand the damaging effect of mispronouncing someone’s name, you have to educate yourself as to why names matter.

In some cultures, names are given that are deeply rooted in social and cultural beliefs. In Ghana, Abadinto (outdooring) is a traditional naming ceremony. This occurs eight days after the birth of the child when parents present their newborn ‘outside’ for the first time to give them a ‘day’ name. A day name is chosen depending on the day of the week and the gender of the child.

In other cultures such as India, an infant naming ceremony is called Naam Karan. It is a tradition where parents, families and relatives make extensive efforts to determine a suitable name for the child, often relying on astrological beliefs.

Our names hold power and should be celebrated. We all should therefore be making a conscious effort to pronounce them correctly. Take a moment or several to ask someone how to pronounce their name. The effort in asking shows a willingness to learn, which is duly appreciated and acknowledged.

Content creator and poet known by her pseudonym simplysayo introduces herself as “Adésayó not Sayo” on her podcast Nailing It, reminding everyone of who she is whilst owning her name.

Having phonetic spelling in your bio or email helps to educate people and alleviate social hesitation. It also helps to normalise the practice for others and makes it easier for those who benefit from it to do the same.

It is worth noting and remembering how different people prefer their names to be said, even if it requires more effort. Taking the time to pronounce a person’s name correctly conveys respect and inclusion and a willingness to treat everyone equally.

We should make saying names a positive experience for everyone. We have the power to promote a more positive, diverse, inclusive and accepting culture and environment.

Take power in owning your name, like I have of mine.